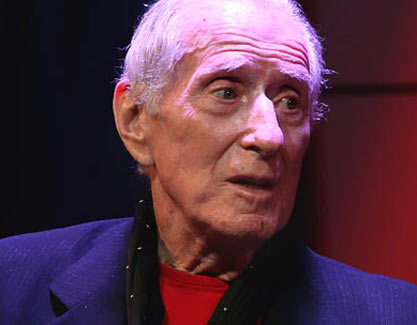

Whilst Jerry Leiber, who died on the 22nd August, may not be a figure that springs immediately to mind in the pantheon of preening, strutting decadents that have shaped popular music, his contribution , alongside Mike Stoller. altered the course of musical history in a way that it has never quite managed to escape from .

Put simply, this rakish son of Polish Jews, through his love of the R and B and jazz music of the 30’s and 40’s, took the street argot from the slums of Baltimore, where he spent his early years and aligned it with Mike Stoller’s rhythmic attacking piano structures to create an array of tough,hip, vernacular lyrics that are instantly recognisable nearly 60 years after their inception.

In creating a lexicon of terms and phrases that still pop up regularly in all genres of music today he was no less than the Dr Johnson of rock and his images, particularly his gift for a scintillating opening line, are known pretty much everywhere by pretty much everyone.

Would you want to spend time in the company of anyone who doesn’t immediately recognise the line

“The warden threw a party at the county jail…”

I wouldn’t. They might be Boris Johnson.

Before Leiber and Stoller, most of the popular songs in the gleaming America of the early 1950’s were wounded tales of being done wrong by some uncaring femme fatale (the subtext being that blokes were basically at the mercy of those evil women creatures) rendered by ageing booze sodden crooners or enervating novelty fare of the “How Much is That Doggie in The Window?” stripe.

In certain cases these two archetypes were melded together in unholy union as in the case of the biggest selling American single of 1953, Dean Martin’s “That’s Amore” .

To those few people who actually got to hear it, Big Momma Thornton’s original version of “Hound Dog” with it’s elasticated opening

“Yooooooooouuuuuu ain’t nnnnnuthin’ but a Houn’ Dog”

and Pete Lewis’s sparking echoless lead guitar running through it until it finally descends into a cacophony of simulated woofs and barks must have sounded like a bomb going off in a lunatic asylum.

Crucially, Leiber and Stoller insisted on producing this record as well as writing it and it spent 7 weeks at the top of the R and B charts where it could luxuriate untroubled by Dino’s pissed up Italianising.

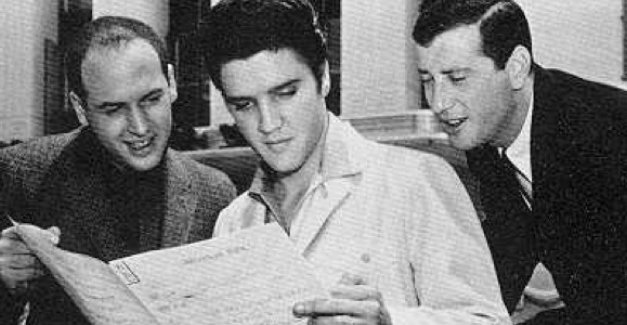

The song went on to be covered by a variety of hipped up country/rockabilly artists (the best of this pretty fine bunch being a booming version on RCA by Jack Turner and His Grainger County Gang should you be interested) until record producer Bernie Lowe asked his then current charges Freddie Bell and The Bellboys to re write the song for a radio friendly audience. It was this version that caught the attention of Elvis Presley who went on as, any fule kno (to quote Nigel Molesworth) to record his own breakneck, clattering version of it to worldwide acclaim. It was at this point that he sought out the songwriters and asked if they had anything else he could use. They had.

The collision of these R&B literate wunderkind with the most charismatic performer of the 20th century cemented Leiber and Stoller’s reputation and they went on to create some of Elvis’ most enduring records , such as Jailhouse Rock, Trouble, King Creole, and Treat Me Nice, and sent Dino, Frank and the others scuttling off back to their casinos to have hushed conversations with men called Vito (allegedly). They also wrote “Bossa Nova Baby ” but everyone’s allowed an off day.

Having altered the DNA of popular music for a generation would have been enough for most , but Leiber and Stoller’s gift was too large to be contained within one artist, even one as phenomenal as Elvis and they also wrote hits for The Coasters and The Drifters, amongst others. To get an idea of how prodigiously talented they were , try and imagine an Elvis version of Yakety Yak or There Goes My Baby – doesn’t work does it?

In his work for The Drifters and Ben E King, Jerry created immense, swelling romatic statements which artfully captured the once in a lifetime period of teenage love when, unburdened by the travails of adulthood, the object of affection is portrayed as the glowing centre of an otherwise unimportant universe. Importantly, it also hints that this feeling can be eternal. Most memorably he did this with Ben E King on “Stand By Me by taking images from Psalm 46 of the King James Bible

God is our refuge and strength,a very present help in trouble. Therefore will not we fear, though the earth be removed,and though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea;

and shaping them into the exquisite

“If the sky that we look upon Should tumble and fall And the mountains should crumble to the sea

I won’t cry, I won’t cry, no I won’t shed a tear Just as long as you stand, stand by me

Forget Brian Wilson – this was the real teenage symphony to God , so epic that it threatens to burst out of the structure of the three minute pop song and take it’s rightful place alongside the works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Andrew Marvell. That it doesn’t is a testament to Stoller’s beautifully understated tune and Sam Appelbaum’s soaring string arrangement.

Â

And you can’t cop off with a pissed up check out assistant from Brighouse at the end of the night to Sonnet 43. Just try it and see what happens

So Jerry was a genius pop songwriter and a poet but what is more often forgotten is that he could be hilariously funny.

In less skilled hands most of the Coasters’ hits would have been inconsequential novelty fluff on a parr with Sheb Wooley’s “Purple People Eater” but Jerry Leiber rooted his lyrics in situations that struck a chord with the teenage audiences. . I’m willing to bet that everyone reading this (hello mum) has at some point in their adolescence felt the underlying frustration of the protagonist of “Yakety Yak” and his/her endless succession of menial chores, or has been to school with someone who seemed to be permanently in trouble for some transgression or other like Charlie Brown

Even when they abandoned this tactic and just rocked out such as on the peerless “Searchin” Jerry deftly incorporated a succession of fictional detectives which although largely forgotten now, would have chimed with the pop culture literate youth of the times

Well, Sherlock Holmes,Sam Spade got nothin’, child, on me,Sergeant Friday, Charlie Chan,And Boston Blackie

No matter where she’s a hiding,She’s gonna hear me a comin’,Gonna walk right down that street,Like Buuuuuuuuulldog Drummond

Â

the last line sung in a sky scraping falsetto that must’ve had Dalmatians howling along the length of the Eastern Seaboard. That the rest of the song seems to pretty much consist of lead vocalist Billy Guy going ” I’m searchin’ against the rest of the group’s insistent “Gonna find her” makes this all the more effective and shows that Jerry knew when to let the music carry the words as Stoller’s bum bap BUM bap piano drives the song along.

As thrilling a two minutes and forty five as has ever existed in pop and one that makes “Three Coins In A Fountain” sound like it was written a hundred years previously.

To list the remainder of Jerry Leiber’s achievements, some well known, some surprising (Did you know that he wrote the words for Shirley Bassey’s “I, Who Have Nothing” or Elkie Brooks’ “Pearl’s A Singer” for example?) would take all day but suffice to say that he leaves behind him a body of work essential for anyone interested in the evolution of popular music in the 20th century and more importantly, some cracking records that still sound as fresh and vital today as they did fifty odd years ago.

In the past I’ve said on this very blog that the exciting stuff in music happens in the margins of popular culture, free from the commercial constraints that seek to render music as a back drop to car adverts and wedding anniversaries.

To take these elements and create something that travels around the world and into millions of lives without losing any of it’s charm or edge is akin to musical alchemy and only achieved by very few people.

Now stop reading this rubbish and go and put some of his records on.

Wooo! go Phil baby!